Jun 15, 2017 The recent release of Joe Jackson’s deeply engaging Black Elk: The Life of an American Visionary (2016) covering all aspects of Black Elk’s varied life—from Oglala shaman and Little Bighorn warrior to Catholic convert and international Wild West entertainer, including even his role in London’s sensational Jack the Ripper criminal. Welcome to Casebook: Jack the Ripper, the world's largest public repository of Ripper-related information! If you are new to the case, we urge you to read our Frequently Asked Questions before moving on to our comprehensive Introduction to the Case.From there feel free to delve deeper into any of the categories below.

- Jack The Ripper Identity

- Black Elk Jack The Ripper Full

- Jack The Ripper Wikipedia

- Black Elk Jack The Ripper Street

Because he was the first celebrity serial killer, Jack the Ripper's victims and their tragic lives were always overshadowed by the man himself.

Wikimedia CommonsAn illustration of the discovery of the body of Catherine Eddowes, one of Jack the Ripper’s victims, as depicted in The Illustrated Police News circa 1888.

Head to London for a dose of the macabre and you won’t be disappointed. Guided tours of the Whitechapel district — where in 1888 legendary serial killer Jack the Ripper brutally cut the throats of five prostitutes and removed their organs — continue to draw in droves of tourists to this day.

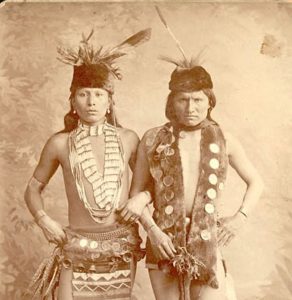

Black Elk, the Native American holy man, is known to millions of readers around the world from his 1932 testimonial, Black Elk Speaks. Adapted by the poet John Neihardt from a series of interviews, it is one of the most widely read and admired works of American Indian literature.

There’s the Jack the Ripper museum, too, which opened last year to controversy. According to historian Fern Riddell, the museum intended to tell the “history of women in the East End,” but activists said the museum mainly “glamorises sexual violence against women.”

Beyond the outcry, it’s not entirely surprising that the museum shifted focus away from Jack the Ripper’s victims and back onto the killer himself. After all, the mystery surrounding who he was and his motivations never ceases to captivate an audience — so much so that there’s a whole field dedicated to the study of his crimes and the discovery of who the Ripper might be: Ripperology.

As some have noted though, at its core this “thriving Ripper industry” is misogynistic, and “commercially [exploits] real-life murder victims.”

Regardless of the truths these criticisms may highlight, fascination with Jack the Ripper and serial killers like him endure and experts don’t see that changing any time soon. As appears in Psychology Today, “the incomprehensibility of such actions drives society to understand why serial killers do incredibly horrible things…serial killers appeal to the most basic and powerful instinct in all of us—that is, survival.”

This, coupled with media market dynamics, helps cement sustained public interest in figures like Jack the Ripper.

Before Jack the Ripper came along, “lurid violence had long been popular with the media” in England, historians Clive Emsley and Alex Werner explained to BBC History Magazine. “When newspapers first became popular in England during the 18th century, editors quickly recognised the value of crime and violence to maintain or boost sales.”

When looking at Jack the Ripper’s violence, editors saw not just murder but revenue, which helps explain how they covered it. In his paper Murder, Media and Mythology, Gregg Jones explains that:

“reporting of the murders did not show sympathy for the fate of the butchered women” because “they were prostitutes and seen to have ‘chosen their profession’…[which] facilitated the continuation of reporting scandal and creating moral outrage but without the need for public sympathy for the murdered women.”

In some respects, these patterns persist to this day: Public fascination with serial killers and the spectacle of violence endures while interest in the reality of the victims (especially Jack the Ripper’s victims) quickly fades.

The women who perished at the hands of the first “celebrity serial killer” led troubled lives and in many ways reveal more about London at the time of the murders than the man who committed them:

Jack The Ripper’s Victims: Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann Nichols led a brief life marked with hardships. Born to a London locksmith in 1845, she went on to marry Edward in 1864 and gave birth to five children before the marriage dissolved in 1880.

In explaining the roots of the separation, Nichols’ father accused Edward of having an affair with the nurse who attended one of their children’s births. For his part, Edward claimed that Nichols’ drinking problem drove them to part ways.

After they separated, the court required Edward to give his estranged wife five shillings per month — a requirement he successfully challenged when he found out that she was working as a prostitute.

Nichols then lived in and out of workhouses until her death. She tried living with her father, but they did not get along so she continued to work as a prostitute to support herself. Though she once worked as a servant in the home a well-off family, she quit because her employers did not drink.

On the night of her death, Nichols found herself surrounded by the same problems she’d had for the majority of her life: lack of money and a propensity to drink. On August 31, 1888, she left the pub where she was drinking and walked back to the boarding house where she planned to sleep for the night.

Nichols lacked the funds to pay for the entrance fee so she went back out in an attempt to earn it. According to her roommate, who saw her before she was killed, whatever money Nichols did earn, she spent on alcohol.

Around 4 AM, Nichols was found dead in the street on Buck’s Row, her skirt pulled up to her waist, her throat slit, and her abdomen cut open. She was the first of Jack the Ripper’s victims.

| Jack the Ripper | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Monty Berman Robert S. Baker |

| Screenplay by | Jimmy Sangster |

| Starring | Lee Patterson Eddie Byrne Betty McDowall John Le Mesurier Ewen Solon |

| Music by | Stanley Black (UK) Jimmy McHugh (US) Pete Rugolo (US) |

| Cinematography | Robert S. Baker Monty Berman |

| Edited by | Peter Bezencenet |

| Distributed by | Regal Film Distributors (UK) Embassy Pictures (through Paramount Pictures) (US) |

| |

| 84 min. | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £50,000[1] |

| Box office | $1.1 million (US)[2] |

Jack the Ripper is a 1959 film produced and directed by Monty Berman and Robert S. Baker. It is loosely based on Leonard Matters' theory that Jack the Ripper was an avenging doctor.[3] The black-and-white film stars Lee Patterson and Eddie Byrne and co-stars Betty McDowall, John Le Mesurier, and Ewen Solon.[4] It was released in England in 1959, and shown in the U.S. in 1960.[5]

The plot is a 'whodunit' with false leads and a denouement in which the least likely character, in this case 'Sir David Rogers' played by Ewen Solon, is revealed as the culprit.[6] As in Matters' book, The Mystery of Jack the Ripper, Solon's character murders prostitutes to avenge the death of his son. While Matters had the son dying from venereal disease, the film has him committing suicide on learning his lover is a prostitute.[7]

Plot[edit]

In 1888, Jack the Ripper is on his killing spree. Scotland Yard Inspector O'Neill (Byrne) welcomes a visit from his old friend, New York City detective Sam Lowry (Patterson), who agrees to assist with the investigation. Sam becomes attracted to modern woman Anne Ford (McDowall) but her guardian, Dr. Tranter (Le Mesurier), doesn't approve. The police slowly close in on the killer as the public becomes more alarmed. The killer's identity is revealed and he meets a ghastly end.

Cast[edit]

- Lee Patterson as Sam Lowry

- Eddie Byrne as Inspector O'Neill

- Betty McDowall as Anne Ford

- Ewen Solon as Sir David Rogers

- John Le Mesurier as Dr. Tranter

- George Rose as Clarke

- Philip Leaver as Music Hall Manager

- Barbara Burke as Kitty Knowles

- Anne Sharp as Helen

- Denis Shaw as Simes

- Jack Allen as Assistant Commissioner Hodges

- Jane Taylor as Hazel

- Dorinda Stevens as Margaret

- Hal Osmond as Snakey the pickpocket

Jack The Ripper Identity

Production[edit]

The film's budget was raised from a combination of pre-sales to Regal Film Distributors at the National Film Finance Corporation.[1]

Black Elk Jack The Ripper Full

Release[edit]

Joseph E. Levine bought the US rights for £50,000. He later claimed he spent $1 million on promoting the movie and earned $2 million in profit on it.[1]

According to Variety, the film earned rentals of $1.1 million in North America on initial release.[2]

Critical reception[edit]

The New York Times wrote, 'the most memorable line of dialogue in Jack the Ripper is read, appropriately enough, at an inquest. In the stentorian tones typical of the new Victorian melodrama, the coroner declaims that the London police are 'incompetent, inadequate and inept.'He may have aimed his verdict at the law enforcers, but visitors to neighborhood theatres this week are likely to give his words a broader interpretation. That coroner would have made a good film critic.' [8]

Jack The Ripper Wikipedia

References[edit]

- ^ abcJohn Hamilton, The British Independent Horror Film 1951-70 Hemlock Books 2013 p 56-61

- ^ ab'Rental Potentials of 1960', Variety, 4 January 1961 p 47. Please note figures are rentals as opposed to total gross.

- ^Meikle, Denis (2002). Jack the Ripper: The Murders and the Movies. Richmond, Surrey: Reynolds and Hearn Ltd. ISBN1-903111-32-3, pp. 75-79. Woods, Paul; Baddeley, Gavin (2009). Saucy Jack: The Elusive Ripper. Hersham, Surrey: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN978-0-7110-3410-5, p. 198.

- ^'Jack the Ripper (1958)'. BFI.

- ^Woods and Baddeley, p. 197

- ^Meikle, pp. 76–77

- ^Meikle, p. 79

- ^https://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9803E0D61138E333A2575BC1A9649C946191D6CF

External links[edit]

- Jack the Ripper on IMDb

Comments are closed.